According to the worldly wise, the end justifies the means.

If one achieves his ambitions, he need not be scrupulous or squeamish for doing what most people do—even if they are dishonest. To overcharge for a product or to prescribe unnecessary medications for a patient for the sake of profit is the way of the world. If a person is clever or cunning enough to succeed and others are gullible or weak, then let the buyer beware.

Machiavelli in The Prince argued that rulers who wish to stay in power must be as bold as a lion or as crafty as a fox. A prince must only appear, not be, good.

Honor and Dishonor

Christian wisdom, on the other hand, teaches that one cannot do evil to achieve good. Both the end and the means must be moral. There is an ethical and an immoral, an honorable and dishonorable, way to succeed and achieve one’s goals. Because Shakespeare’s Macbeth aspired to be king of Scotland, he justified his murder of King Duncan and chose treachery to his king, his kinsman, and his guest to gain his ambition. Hamlet, however, sought justice for the murder of his father, but he did not wantonly act out of revenge.

The world says “Might is right.” Tyrants determine the meaning of lawful and illegal, justice and injustice. The political party in power changes laws and reinterprets morality to suit its agenda and ideology. The Supreme Court is the final arbiter of right and wrong, constitutional and unconstitutional. It determines whether or not slavery is legal and whether or not abortion is the killing of an unborn human life. Truth is relative to time, place, and the political party in power. Truth is always changing, and nothing is absolutely truth for all people, in all times, and in all places.

Christian wisdom, on the contrary, teaches that an unjust law is no law at all (mala lex, nulla lex). All human laws must conform to the natural law, the God-given knowledge of right and wrong written on the human heart and conscience that St. Paul alludes to in his letter to the Romans: “When Gentiles who have not the law, do by nature what the law requires, they are a law to themselves, even though they do not have the law.”

Without the knowledge of the Ten Commandments, the Romans and Greeks know the moral law by nature. As C.S. Lewis proves in The Abolition of Man, all the cultures and religions of civilization share universal moral truths such as “Duties to Parents, Elders, Ancestors,” “Duties to Children and Posterity,” and “The Law of Good faith and Veracity.”

Minimum Expense, Maximum Gain

The world defines prudence as enlightened self-interest, foresight on behalf of one’s self for the sake of profit, the ability to calculate and guarantee that what one gains surpasses what one loses. It is the artfulness of giving in order to receive, of doing the minimum and expecting a fortune, and of cultivating friendships that will produce benefits for one’s career.

Worldly prudence is what Shakespeare’s villain Iago calls serving others to serve himself. As Shakespeare’s spy Polonius epitomizes the extreme wariness of worldly wisdom when he counsels his son, “Give thy thoughts no tongue,” “Give every man thy ear, but few thy voice,” “Neither a borrower nor a lender be.” In other words, watch out, be careful, trust no one, take no chances. Polonius’s famous words, “To thine own self be true,” mean that self-interest is the motive of all human actions.

Christian wisdom, however, calls the cardinal virtue of prudence the first of the four natural virtues, the understanding of what is right and good that governs justice, fortitude, and temperance. The cardinal virtue of prudence is foresight on behalf of others, not narrow self-interest. Prudence foresees the consequences of actions as they affect one’s family, the common good, and future generations. Human prudence imitates God’s Providence that orders all things for the good—the vision of seeing both the good of the whole and the good of the part.

Christian prudence is not ruled by fear or caution but acts with courageous boldness to achieve heroic ideals. Huckleberry Finn’s daring chances to hide and protect the runaway slave Jim from unjust laws and from cruel slave hunters illustrates the cardinal virtue at its best—thinking ahead for the sake of others.

Planning, Power and Perspicacity

Worldly wisdom views life as a chess game in which the best players outmaneuver their opponents by ingenious strategy. They trust in shrewdness and rule out altogether the element of chance or luck. Plotting calculated moves and thinking ahead of the opponent’s countermoves, the worldly chess player comes to believe that all success depends upon careful planning, the will to power, and man’s shrewd intelligence. If life is a merely a political chess game played by masters who predict outcomes, then man is a god, and no Divine Providence orders human affairs or surprises history with miracles.

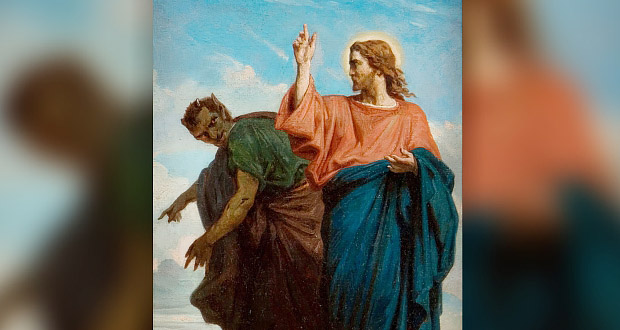

Christ, however, blesses the pure in heart, praises the Israelite in whom there is no guile, and praises honest speech that says without dissimulation “yes, yes” and “no, no.” Christian wisdom inspires man not to be anxious about the future or to attempt to predict it. It teaches man to be both as wise as a serpent and as gentle as a dove—neither relying on cunning for success nor being naive about the artifices of evil.

While worldly wisdom presumes to predict the future according to economic laws, political forces, or grand theories of progress, Christian wisdom acknowledges the Lord as the God of wonder, mystery, and awe whose thoughts and ways are not man’s thoughts and ways.

Andersen’s “The Emperor’s New Clothes” illuminates the difference between these two types of wisdom. The weavers lie about the beautiful garment they pretend to sew for the king by inventing the fabrication that the ignorant and incompetent are not qualified to appreciate it. The courtiers and officials of the court pretend to see the beautiful cloth that does not exist because they fear losing their position or ruining their public image.

The crowds who watch the king march naked during the procession all agree that the king looks handsome because they assume the elite and sophisticated know best. The weavers trick, the king pretends, the courtiers lie, and the crowds copy for the sake of profit, vanity, popularity, or reputation. “To thine own self be true.”

But the truthful child who cries, “But he’s nothing on,” untangles the sophisticated complication of worldly wisdom that ensnares the gullible who dare not say “no, no” at the sight of the naked king but instead parrot “yes” when they really mean “no.”

Seton Magazine Catholic Homeschool Articles, Advice & Resources

Seton Magazine Catholic Homeschool Articles, Advice & Resources